Linear A: A Language Unknown

There are thousands upon thousands of languages. Some languages are thriving, like the ones we might know without even learning: English, Spanish, French, etc. Some languages only have a handful of speakers and are in danger of dying out. Some languages are considered “dead,” where they still have prominence but no people actually speak them. However, some languages and their resources have been completely lost to time, and it’s only possible to hypothesize their origins. One such case is the Linear A writing system, used by the Minoans of Crete over 3000 years ago.

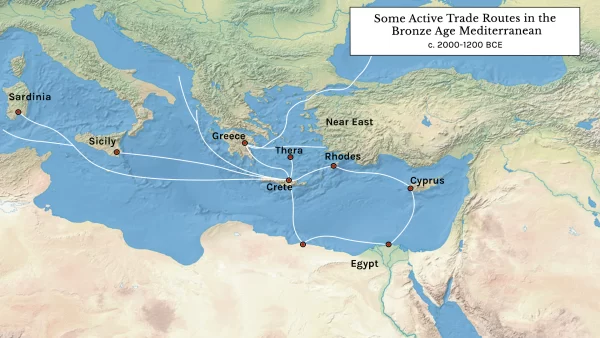

During the Bronze Age, this Linear A writing system was the dominant form of communication in the Minoan civilization. From 1850 to 1450 BC, this language was quite popular in Crete. The Minoans were a civilization that flourished in the Bronze Age and were known for their settlements of Knossos, Phaistos, and other city-like organizations. These areas were centered around a palace, which was a center of commerce for the entire city, and they all resembled labyrinths in their construction. Any surplus valuable materials, like wine, grain, and oil, were stored in these palaces.

During the Bronze Age, this Linear A writing system was the dominant form of communication in the Minoan civilization. From 1850 to 1450 BC, this language was quite popular in Crete. The Minoans were a civilization that flourished in the Bronze Age and were known for their settlements of Knossos, Phaistos, and other city-like organizations. These areas were centered around a palace, which was a center of commerce for the entire city, and they all resembled labyrinths in their construction. Any surplus valuable materials, like wine, grain, and oil, were stored in these palaces.

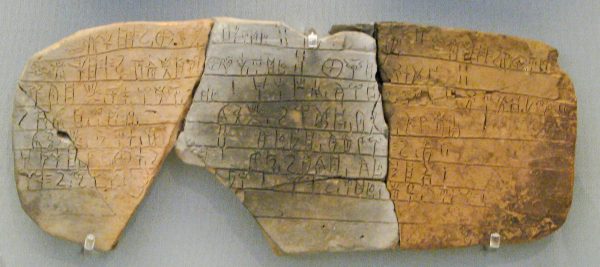

A series of devastating earthquakes destroyed these palaces around 1700 BC, but they were rebuilt and survived until more earthquakes arrived in 1450 BC – though they could have also potentially been due to fires or invasions. With their collapse, the Minoans took their writing system with them. Historians have agreed that the main purpose of Linear A was to administrate trade transactions, like the exchange of food, cattle, and other goods. Some of the clay tablets that Linear A was inscribed on could also contain personal information for certain traders or even their authors. None of this information is officially determined, however, since the writing system has yet to be fully deciphered. According to historian V. La Rosa, there is potential for the tablets to describe “inputs and outputs from the storerooms, to the distribution of goods in exchange for work, to transactions, and perhaps also to taxes.”

Linear A has also been discovered on clay disks, which are theorized to have been used as receipts. They usually had inscriptions on both sides. Some disks were found to have central holes or were used as seals for pots and other large hollow objects. Jewelry, weaponry, and even tables have also been found with the Linear A writing inscribed on them. These inscriptions were longer than most of the ones already discovered on clay tablets, and they were likely proper nouns like the name of the creator or the name of a deity it was dedicated to.

The writing system has even been found in architecture, as stone blocks and walls have been found with Linear A. This, however, was written in ink, which was a deviation from the carvings that had been found in clay tablets. With their language in tow, the Minoans and all their goods traveled all across the Mediterranean Sea. Trianda, a Minoan site, became a major trade hub during the Bronze Age. Linear A has been found on the islands of Santorini, Kythira, Samothrace, and Tel Harror among others.

After the fall of the Minoans, they were replaced by the Mycenaean culture. Knossos, one of the biggest cultural hubs of the Minoans, was potentially left standing for another century, but it too collapsed due to unknown factors. Most traces of the Minoans were almost completely wiped out by 1200 BC. Elements of Linear A made reappearances in the Mycenaean’s writing system, titled Linear B. The only potential way Linear A could be deciphered is a Rosetta Stone, where a large sample of the language appears in comparison to other languages and can be decoded from there.

After the fall of the Minoans, they were replaced by the Mycenaean culture. Knossos, one of the biggest cultural hubs of the Minoans, was potentially left standing for another century, but it too collapsed due to unknown factors. Most traces of the Minoans were almost completely wiped out by 1200 BC. Elements of Linear A made reappearances in the Mycenaean’s writing system, titled Linear B. The only potential way Linear A could be deciphered is a Rosetta Stone, where a large sample of the language appears in comparison to other languages and can be decoded from there.

St. John’s College professor Dr. Ester Salgarella took this comparison to the next level and used interdisciplinary methods to approach potential solutions for Linear A by contrasting it with Linear B. She created a database of both languages to accurately analyze them and was even able to make some connections between the two. Some Italian researchers from Bologna also tried to decode the language by using mathematical quantities and comparing them to Minoan artifacts. Despite this, most of Linear A remains a mystery.

Linear A might only be truly deciphered if more examples of its use are uncovered. Thousands of languages have been lost to time, and Linear A is only one. Understanding these languages can open up worlds of new information from civilizations that remain lost to time.