Reed Books: Fahrenheit 451

December 5, 2019

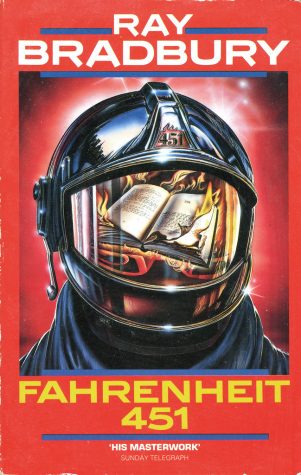

“It was a pleasure to burn.”

These six words start one of the most read books in modern history – Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury. Published in 1953, this dystopian novel serves as a cautionary tale to the government-weary American population in the years after World War II. After suffering such a long, brutal battle, America was jolted into an economic boom. Still, the horrors of the war from less than a decade before haunted the minds of the general population. Tales of Nazis breaking into homes, stealing valuables, killing, and burning books served as inspiration for Ray Bradbury’s classic tale.

Guy Montag, a fireman in future America, is one of the many men who burn books for a living. The government finds this as an efficient way to stop the spreading of information, thus leading to a gullible and easily-led population. However, natural human curiosity gets the best of Guy, who smuggles books into his home. While he barely touches them in the beginning of the novel, Guy becomes progressively more obsessed with them, trying to convince his wife, Mildred, and many others to read them with him. He is thrown out of society, and stays on the lam with a ragtag group of former intellectuals who attempt to rebuild the world they know.

One of the most important characters is Montag’s neighbor, a teenage girl named Clarisse. Free-thinking and radical, she rants about freedom of speech and thought, before disappearing, apparently dying in a “car crash”. Montag suspects otherwise, but never explores that plot.

While the most obvious theme in Fahrenheit 451 is the repression of free thought and speech by dictatorial governments, the novel is much deeper than that. As readers travel through this fictional world, we discover the disturbing obsession with entertainment. Televisions cover every wall in some rooms – cars go hundreds of miles an hour, killing people for sport. Even the manhunt for Montag is filmed as a reality TV show, and ended with an innocent man being killed so the audience may consider themselves safe. As long as people are distracted from the main issues, they are happy. The old Roman saying – “bread and circuses” – fits the novel perfectly.

Still, under all the pessimism, there is a certain rough hope about the book – that people will find a way to rebuild.

When Montag reads the poem “Dover Beach” to his wife and her friends, Mrs. Phelps, a neighbor, begins to cry. She is confused by her own emotions, but still feels them. Clarisse, even as a younger character, knows this way of life is wrong, and doesn’t hide it from anyone. Montag, despite not knowing why, is compelled to sneak books away, to read them in secret. The human spirit of curiosity will win out over everything, even the conscience knowledge of those people. This is emphasized in the last few lines of the book, as another survivor talks to Montag. He compares humanity to a phoenix – dying and being reborn, forever. But people have something the phoenix doesn’t: memory. We can remember and learn from our mistakes, the man explains, so we won’t have to keep dying and reliving.

After World War II, this was the message that America needed. To know that with every generation, it will get better. People will remember, and people will change. History can not be kept a secret for long.

For such a heavy book, the lesson is surprisingly hopeful; a bright flame, burning, in the dark.