A Story of American Student Activism

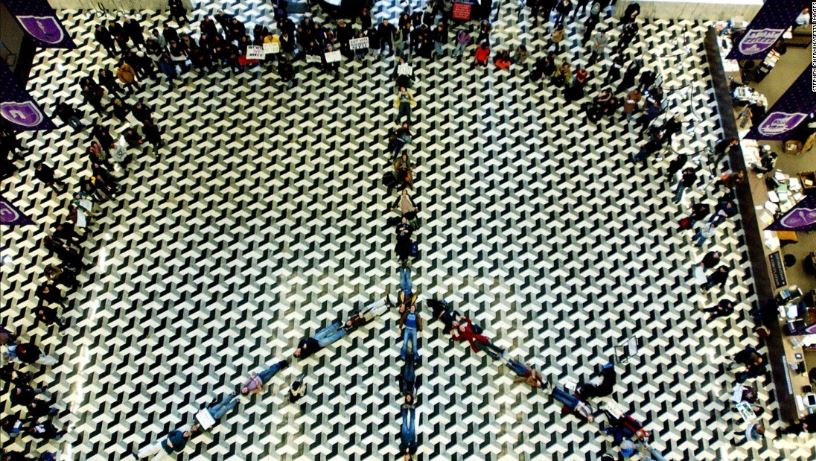

2003, New York University. Students lay down on the floor of the NYU library to protest the impending war in Iraq.

February 7, 2018

In the past years, America has seen numerous college protests held in an attempt to bring attention to a variety of causes from rampant social injustice to abolishing grades below C.

Campus protests have become the new norm: one can expect to hear about at least a few of them every month from all across the country. But have these acts of student defiance really been effective?

The first student protest recorded in America took place at the renowned Harvard University in 1766. One day, dinner at the college was served with very rancid butter. Outraged, Asa Dunbar, the grandfather of Henry David Thoreau, exclaimed, “Behold, our butter stinketh!” He got punished for insubordination, and, the next morning, other students protested this by leaving their hall, cheering in Harvard Yard, and going out to dine in town. Thus, a quintessential part of America’s student activism was born.

However, student protests didn’t really gain traction until the 1960s, when they prevailed with the anti-war, student, and civil rights movements. In 1960, numerous student groupings formed, including Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which fought for equality, economic justice, peace, and participatory democracy. One of the largest and most influential radical student organizations of the time, the grouping became best known for its efforts against the Vietnam War. The The activism of SDS and other similar movements across American campuses, involving mass demonstrations and, notably, “teach-ins” on Vietnam, resulted in a profound shift in the public’s perception of the war, and unexpectedly the government. If before the movement Americans would accept their presidents’ foreign policy leadership almost unquestioningly, following the protests Americans demanded a transparent debate on foreign policy. Eventually, the government reduced the US troop presence in Vietnam and eliminated the draft (while also authorizing the FBI/CIA to expand their surveillance/harassment of antiwar protest groups…but still!).

Initially, most people disapproved of these movements, but, slowly, Americans accepted them. The protests altered the mindset of the public in fundamental ways, on a wide range of topics, proving that the actions of a passionate collective can have a profound effect. Perhaps, these promising statistics played a part in the recent rise in student activism.

A 2016 survey by UCLA revealed that at least 9% of the incoming freshman class expected to participate in student protests – an increase of 2.9% from the similar 2014 survey, and as our country uncovers more and more divisive issues that urge students to speak up this number is expected to continue growing. There were 40 protests at Syracuse University from 2012 to 2017 – compared to just 16 protests from 2007 to 2012. In 2015, 160 student protests took place just during the fall semester.

Today’s student protests changed little from the 1960s. The themes on their forefront remain those of racism and student rights (with the additional topic of sexual assault). As New York University history professor Robert Cohen put it, “Today’s protests, like those in the ’60s, are memorable because they have been effective in pushing for change and sparking dialogue as well as polarization.”

In 2016, a student from Duke University, after learning about the inferior working conditions many textile workers in third-world countries have to endure, collaborated with students from other colleges to organize the Sweatshop-Free Campus Campaign. After studying international labor standards and monitoring mechanisms, the group drafted a code of conduct for college campuses establishing that sports-apparel manufacturers would be able to obtain a license only if they eliminated sweat-shop working conditions for their employees. Multiple protests against sweatshops were held at Duke, and, over time, the school administration recognized the demands of the demonstrators. Duke became the first campus to adopt a code of conduct requiring a process for monitoring manufacturers of college-licensed products, followed by numerous schools across America. The campaign currently continues to work to pressure the Collegiate Licensing Company, the licensing agent for some 170 institutions, to adopt the Duke code.

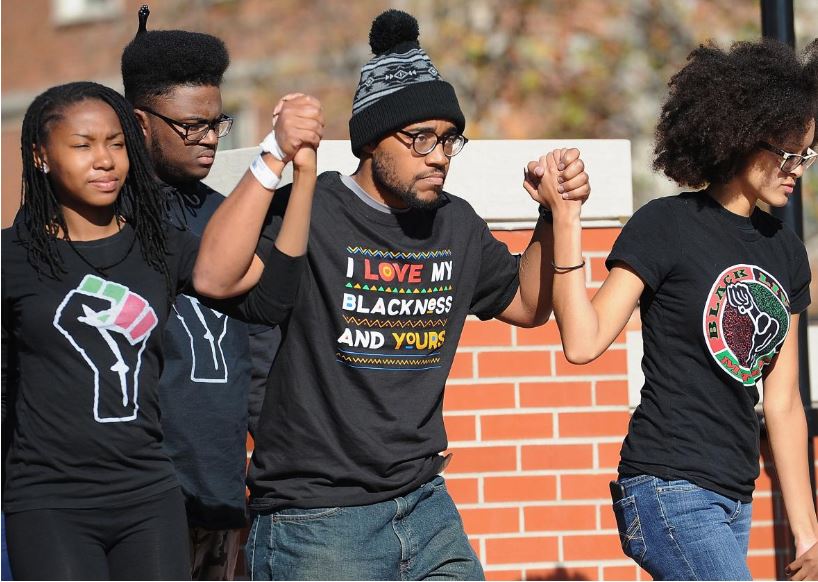

A different protest took place during the Fall of 2015 at Missouri University, over a series of racist incidents on campus. Following mass demonstrations and the football team’s strike, on November 9, the President and the Chancellor of the university announced their resignations (caused in part by factors that happened prior to the protests). The university’s Board of Curators also announced that it was enacting a series of diversity initiatives, such as the appointment of a chief diversity, inclusion, and equity officer and efforts to hire more faculty members of color.

The initial Missouri victory was seen as a breakthrough for student protests, sparking a wave of activity across the country. But the university itself hasn’t been faring so well recently: after 2015, freshman enrollment at Mizzou dropped by more than 35 percent, the university gaining a reputation of a place lacking in diversity and tolerance. Still, some faculty members expressed hopes that the the legacy of the protests will live on to create change.

As shown by Missouri University, on their own, the protests will not be effective. The underlying causes of these issues on the college campuses, and in our society, must be addressed for anything to reform. The general population needs to become invested in these topics, pressuring the government to act. Despite all, the college protests, heavily covered by the media, are effective in forcing these problems to the forefront of the public view, making them far harder to ignore. Perhaps, like their 60’s precursors, today’s activists will succeed, bringing about an unprecedented level of justice and equality.

All images courtesy of http://www.cnn.com/2017/04/18/us/gallery/college-campus-protests/index.html